A NEW KERA NEWS SERIES: Proton beam ray-guns were the stuff of scientists and sci-fi writers in the '50s. But, they never left the lab or the movies. Later, President Reagan revived the idea in his "Star Wars" missile defense initiative. Still, no one really harnessed this atomic age technology until doctors deployed it and made proton therapy a battlefield breakthrough in the war on cancer.

David Richard was just a toddler when the U.S. exploded the first atomic bomb in the desert of New Mexico in 1945.

Today, he’s 69, lives in McKinney and has prostate cancer. He’s getting proton therapy at a treatment center in Oklahoma City – using technology that’s a direct descendant of that first atomic blast.

Richard’s cancer diagnosis was just his latest call to action. He spent 42 years as a helicopter pilot in the Army.

“I served two tours in Vietnam where I was shot down nine times,” the veteran says. “The worst thing that happened to me is I was poisoned with a punji dart. I ended up spending a little time in the hospital and got over it.”

Time in the hospital did not appeal to Richard when he was diagnosed earlier this year. His doctor recommended surgery.

“In which they’ll give you a cut at the lower part of your abdomen, about 12 inches across there,” says Richard. “So I was really hesitant to proceed with that line of treatment.”

A friend at church told him about something called proton therapy. Two proton treatment centers are in the works for North Texas, in Dallas and Las Colinas. But, they won’t see patients for a few years. So, Richard went to ProCure in Oklahoma City for nine weeks of daily treatments.

Dr. Gary Larson, a radiation oncologist there, says proton therapy kills cancer cells the same way conventional radiation therapy does. But here’s the difference. A proton beam can be controlled to provide the biggest blast to the tumor with the smallest radiation spillover to healthy tissue.

A promotional video outlines how proton therapy works. (Courtesy ProCure.)

The process begins in a very large room that patients never see.

“We take hydrogen gas and heat it to a plasma so we can separate out of the protons and electrons, and then accelerate the protons themselves so they are at a very high energy,” Larson says.

That’s done in a 220-ton cyclotron. It revs-up the protons to 60 percent of the speed of light. Then large magnets direct the proton beams to four treatment rooms.

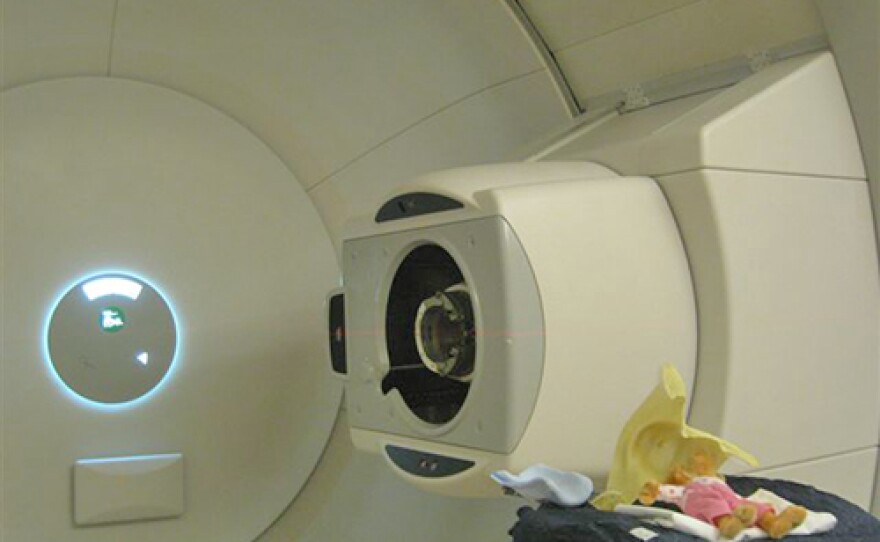

That’s were radiation therapist Dane Hinten comes in. His room looks like something out of Star Wars. Huge pieces of connected equipment fill the walls and curve across the ceiling. The main feature looks like a giant camera. And through that big “eye” comes the proton beam.

“This is our robotic table,” Hinten says, giving a tour. “This is the table the patient actually lies on.”

Here’s where things get really precise. Each patient gets a custom-made aperture. It’s made of brass and cut in the exact shape of the patient’s tumor. It controls the path of the proton beam. Another custom-made piece is called a compensator. The thick block of blue wax is placed next to the patient is carved out in a way that directs the proton beam.

“On the average, proton therapy delivers about 60 percent less radiation to healthy tissues than conventional radiation therapy does,” Larson says.

It is expensive, generally twice as much as conventional radiation therapy. Basic cost is about $40,000 per patient; more for certain cancers. Larson says most insurance covers it. He’s grateful for advancements that began on the battlefield and are now helping his patients.

BONUS: NPR Looks Into The Controversy About The Cost Of Proton Therapy.

“We got Cobalt 60, which didn’t exist before there was an atom bomb, which we used for many years for radiation therapy,” the doctor says. “Strontium 90 is another isotope which we use in treating some eye tumors. We have fortunately learned to use protons for being a very effective agent for treating cancer.”

David Richard, the North Texas Army veteran being treated in Oklahoma, is a believer.

“If I had an object to be removed from my body, would I want them to use a sparkler to burn it out or would I want them to use a very direct, straight line laser-type device?” he asks. “So, I’d say that’s pretty close shootin’.”

Coming Tuesday: In part two of our Battlefield Breakthroughs series, Courtney Collins looks at how robots are remaking cancer surgery.