In Texas, organizations that work with victims of sexual violence are seeing more women and men coming forward to report assaults this year.

One Tarrant County group has seen a 9 percent increase in calls from victims since January. It’s not entirely clear what is behind the trend, but the increased demand for services for sexual assault survivors comes as sexual harassment and violence have made national headlines.

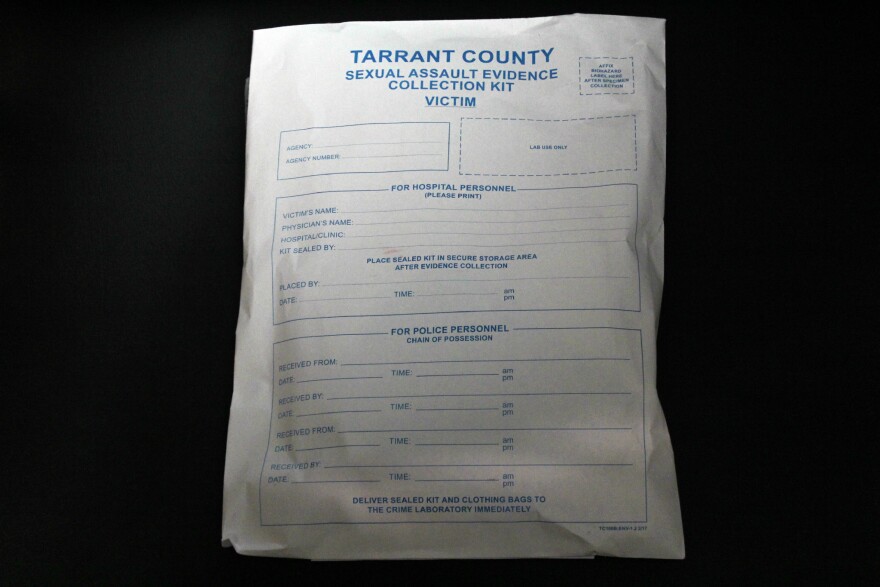

At John Peter Smith Hospital in Fort Worth, which handles sexual assault examinations for nine counties, Connie Housley says they’ve seen more people come in seeking medical and other services for sexual assault this year, including a large spike in July. Housley runs a team of sexual assault nurse examiners who are trained to work with victims and collect forensic evidence for rape kits.

“We’ve seen a lot of things in the media about sexual assault and sexual harassment, and some support for the victims,” Housley said. “I’ve actually had patients tell me that that’s why they came — because they thought somebody would believe them."

The Women’s Center of Tarrant County has seen a 9 percent increase in calls for victim advocates so far this year, compared to the same time period last year. These volunteer advocates are deployed to area hospitals when patients come in after experiencing sexual violence to help them understand their legal and other options, and connect them with services they might need.

Alisha Byerly runs the victim advocate program for the women’s center, and says she started noticing an uptick in calls at the end of last year.

“Winter holiday months are typically a little bit slower, but we saw a pretty dramatic increase during that time,” compared to the previous year, Byerly said.

The Texas Association Against Sexual Assault has been surveying rape crisis centers across the state. Chris Kaiser, the group’s director of public policy, says Tarrant County isn’t unique.

“Across the board right now, all of those programs are telling us they’ve seen a spike in the demand for their services,” Kaiser said.

MeToo’s effect on the ground

It’s been nearly a year since allegations of harassment and assault were leveled against Hollywood movie producer Harvey Weinstein, leading to his ouster and unleashing waves of women and men coming forward to tell their stories of sexual violence and harassment, a movement crystallized under the hashtag #MeToo.

Soon after, famous men who had reportedly harassed and assaulted with seeming impunity were being called out, in the news industry, on Wall Street, in churches and in politics. By the end of the year, Time Magazine named the so-called Silence Breakers, survivors who spoke out, as the magazine’s 2017 Person of the Year.

While advocates say it’s reasonable that this movement would prompt survivors to feel more comfortable coming forward to ask for help, it’s not clear that accounts for the uptick entirely. It is possible that there is also an uptick in assaults, though reliable data on sexual violence is difficult to collect for a variety of reasons. Many victims never seek help from medical professionals, rape crisis centers or law enforcement.

The prevalence of sexual violence in Texas

A 2015 report by researchers at the University of Texas estimated that one-third of adult Texans had experienced some form of sexual assault. Women, the study found, were twice as likely as men to be assaulted in their lifetimes.

There is no standard experience of sexual violence, according to Connie Housley, the JPS sexual assault nurse examiner. She sees victims across race, class, gender, age and experiences.

But, Housley says, there are common misconceptions. Despite more common portrayals of sexual assault on TV, most victims already know their perpetrator, Housley says, and that often adds to the trauma.

“They’re people in our circle, or they’re people we thought we could trust,” Housley said. “And there’s a lot of emotions that go along with that. There’s a lot of self-blame with our patients.”

Housley says many victims delay asking for help or telling a confidante after they’re assaulted by somebody they know. They may fear reprisal if they report the assault, and Housley says some worry about what might happen to the perpetrator. Others may not immediately register that the unwanted sexual contact was an assault. Stigma is also a barrier. Lately, though, Housley says she’s seeing more cases where people come into the hospital long after a sexual assault to get help.

A public health problem

The 2015 UT study also found that just 9 percent of victims reported their assault to law enforcement. Under Texas law, adult victims of sexual assault can seek help at rape crisis centers and hospitals without reporting the crime to law enforcement. They can even have forensic evidence taken, which is held for two years to give survivors time to decide whether to press charges.

That helps to explain a discrepancy in Tarrant County: So far this year, the Fort Worth Police Department has actually seen a decrease in sex crimes being reported, at the same time that the county hospital and the women’s center are seeing increased demand for their services.

“This is really a public health issue,” Kaiser said. “We talk about sexual assault in the criminal justice system almost by default in this country, but the fact of the matter is most sexual assault survivors don’t engage with those processes.”

Still, Kaiser says all victims are at dramatically higher risk than the general population for a range of medical and mental health problems, and he hopes that seeing high-profile sexual violence perpetrators face justice can help reduce the stigma that might prevent a survivor from seeking help.

“The research shows that advocates and counselors at rape crisis centers will improve those people’s outcomes," Kaiser said. “Seeking those services can really help somebody keep their lives on track after something really bad happened.”

Struggling to meet demand

But Kaiser says a consequence of more survivors seeking services is that it strains the state’s rape crisis centers, many of which are already operating at or close to capacity. He worries what might happen if victims face backlogs and waitlists for counseling and other services.

“We’re talking about people in acute trauma, in crisis,” he said. “If they show up at the door saying, 'I need to talk to someone to help me process something that just happened'….and they’re told, 'Well, it’s going to be three weeks before you can talk to a counselor,' they’re very likely to drop off and never come back.”

At the Women’s Center of Tarrant County, Alisha Byerly says they’re feeling the pinch. In addition to increased calls for victim advocates to accompany people to the hospital for a sexual assault exam, the center is also fielding more calls to their hotline about counseling services and fielding inquiries about pursuing criminal charges for sexual assaults.

“We are in desperate need of more people who want to come out and volunteer and help support survivors in Tarrant County at the hospital and on our hotline,” she said.

The center is holding three information sessions in September for people who are interested in volunteering, either as victim advocates or in other capacities at the center, all of which require some training.