In the era of U.S. slavery, it was illegal for African-Americans in many parts of the country — both enslaved and free — to learn to read and write.

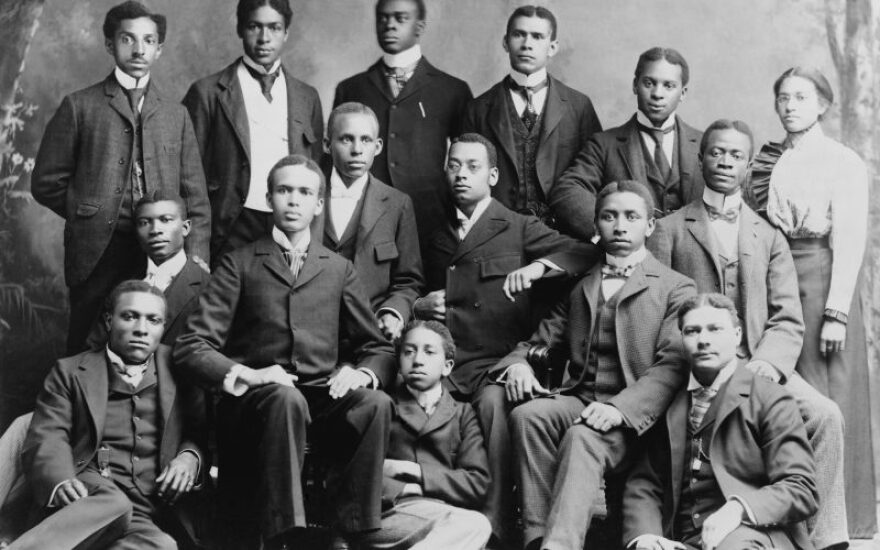

But millions who were denied that right understood the power of education. By the late 19th century, there were dozens of black colleges in the United States.

Filmmaker Stanley Nelson has produced a new documentary for PBS that looks at how leaders like Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Du Bois had different ideas about the kind of education black Americans needed after the Civil War and into the 20th century.

On Think, Nelson talked about how black colleges served as an incubator for civil rights activism, why it took so long for those schools to have African-American presidents and how they helped redefine what it meant to be black in America.

Interview Highlights

Why the education of African-Americans was feared

White Americans were fearful of black Americans getting an education. It was illegal not only for slaves to learn to read and write but also for their so-called masters to teach them.

“If you can imagine being enslaved in the South, that’s the only world you know," Nelson said. "It’s a pretty all-encompassing world. And you can understand why education was something to be feared."

Between 1866 and 1872, 20,000 African-Americans were killed across the South by white people who didn’t want them empowered by education, according to Nelson’s documentary.

“Schools were burned, people were run off, and people were killed,” he said.

The elite in the South didn't want white people who were poor to be educated, either. And there was pushback against education of black Americans in the North as well during this time.

On white administrators at black colleges

Early black colleges had white administrators who, on one hand, wanted to educate African-Americans, but on the other hand, aimed to perpetuate black inferiority.

“Many of the people who went to the South — white folks from the North — were well-meaning, but there was still this idea that African-Americans were inferior,” Nelson said. “‘You know, they don’t really need to be reading the classics; mathematics may be a little bit too much, but we’ll do what we can.’”

For decades, the boards at these black colleges were made up of white people, and therefore, the funding and decisions came from white people.

“Up until the ‘30s and ‘40s, even later for some colleges, the black colleges were run by white people,” Nelson said.

On the education of Booker T. Washington versus W.E.B. Du Bois

Booker T. Washington was born a slave and later freed after the Civil War as a young man. He worked as a laborer but wanted an education. He walked across Virginia to the Hampton Institute, which pushed for an “industrial education,” essentially an education for service.

Washington graduated and went on to become one of the few black college presidents. He led the Tuskegee Institute and preached what he was taught: an education for service. This level of black education was comfortable for white Americans in the South and North at the time.

“He is, I would argue, the most famous African-American and the most powerful African-American at the turn of the century,” Nelson said. “He’s a college president — that’s how important education was seen at that time.”

Some thought Washington’s philosophy for success was dangerous for the African-American population and its progress.

In many ways, W.E.B. Du Bois is the exact opposite of Washington, Nelson said. He grew up in Massachusetts, went to Fisk University, then onto Harvard and finished his studies in Berlin.

He broke from Washington, saying that African-Americans needed to be educated at the same standards and quality as white students.

“This sets up this epic battle that goes on for years with Du Bois and other scholars, pushing against Booker T. Washington’s vision of industrial education,” Nelson said.

Map of HBCUs from U.S. Department of Education

View this map in a separate window.

Trailer for Nelson’s documentary

Nelson’s new Independent Lens documentary “Tell Them We Are Rising: The Story of Black Colleges and Universities” airs at 9 p.m. on Feb. 19 on KERA-TV.

To listen to the entire interview, stream or download it or subscribe to the Think podcast.

More on HBCUs

» KERA Think: Listen to our episode about the untold stories of HBCUs.

» KERA Learn: View our map of HBCUs in Texas.

» KERA TV: Watch our CEO episode with Dr. Michael Sorrell, president of Paul Quinn College.