Telemedicine, which connects doctors and patients virtually, has made a big difference in North Texas schools for students with physical issues.

This fall, the same technology will be available to connect students and their behavioral therapists in a pilot program from Children's Health.

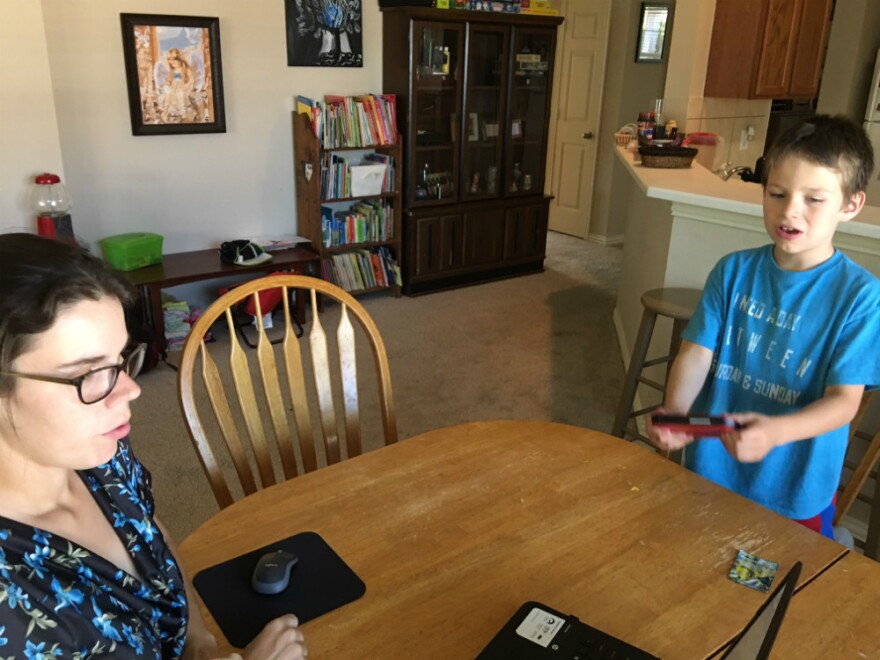

Therapy at the kitchen table

Jessica Masters' children's squeals pierce the calm. Her hands are full. She and her husband are raising three young kids in their Royse City home. She says her oldest, Josh, who’s 8, can be especially rambunctious.

“When he was a baby, he started running before walking," she says. "He runs everywhere.”

“I don’t like walking,” Josh yells from the other room.

“See?” Masters says.

Josh may not like walking, but he manages to settle down enough for his online appointment with therapist Angeleena May. She’s a licensed professional counselor with Children’s Health, near downtown Dallas.

“Hi, Miss Angeleena,” Josh says.

“How are you?" May replies.

“Good,” Josh says.

Their appointment’s not in an office. Josh is on a laptop in the kitchen. He has Attention Deficit Disorder with hyperactivity and anxiety. That makes it hard for him to sleep at night and as a result, hard to stay awake in school the next day.

Once a week, he meets with Miss Angeleena. Masters likes that Josh and his therapist are able to meet virtually, saving the 35-mile trip to Dallas, and her son doesn't have to miss school.

"He can just do this with her after school, and we don’t have to go to the doctor,” she says.

She says it saves her time, hassle and money, and Josh gets what he needs. She calls it awesome. And Josh?

“Super awesome!" he says.

“Super awesome?" Masters says.

“Because," Josh says, "it’s super cool that I got to see her on the computer.”

Accessible mental health care

Connecting from home also reduces anxiety. For a time, Josh feared appointments in Dallas, worried he might get poked, prodded or injected.

This home visit’s a test run. When school starts in August, Children’s Health will arrange private therapy visits via telemedicine in a few select schools. Tony Walker understands the need.

“Twenty percent of school-aged children would be diagnosable with some sort of significant mental health issue," Walker says. "But only 5 percent of those kids have actually been identified, and so we know that it’s a huge concern.”

"We knew that the only way that we could really create the opportunity for more access was really through technology."

Walker is the director of student support services at Uplift Education, which has 17 charter campuses in North Texas.

This fall’s pilot program starts in the Carrollton-Farmer's Branch District, and Dallas ISD is considering it.

Mental health issues can range from suicidal behavior and self-injury to depression or, in Josh’s case, anxiety. All can interrupt learning, yet almost all can be helped — though not without obstacles.

“There’s a stigma for mental health [and] behavioral health issues in the community," Jason Isham says. He manages behavioral issues at Children’s Health.

“One of the ways that we want to combat that is by providing rapid access to folks in the areas where they live and they work and they play,” Isham says.

“There’s a shortage of pediatricians and a shortage of psychiatrists and psychologists," Danielle Wesley at Children's Health says. "We knew that the only way that we could really create the opportunity for more access was really through technology.”

Wesley, director of Children's Health campus-based programs, says the hospital has already been using digital devices for physical checkups. One advantage for behavioral telemedicine is that there’s very little gear.

She’s optimistic behavioral services will grow the way physical exams have.

“We actually have a waiting list of school districts that are calling us about our model,” Wesley says.

Lancaster’s superintendent told her he saved the district half a million dollars.

Deep breaths

Back in Royse City, Angeleena shows Josh some red, squishy balls that he can squeeze to help relieve anxiety. She then asks him how he might try to fall asleep quicker. His mom suggests maybe he could stop throwing fits when it’s bedtime.

“I throw a fit because I want to watch TV," Josh says. "I want to finish 'Henry Danger' and 'Full House'!”

May senses a change. “Josh, this would be a good time to do a couple deep breaths," she says. "It seems like you’re a little upset."

Josh takes a few deep breaths.

"There you go." May says, "Good job.”

Stress ball in each hand, Josh then squeezes them as he takes some more slow, deep breaths and calms down.

He tells May that it helped him feel better. Then, Mom to the rescue, reminds Josh that "Henry Danger" and "Full House" are recorded, so he can watch tomorrow.