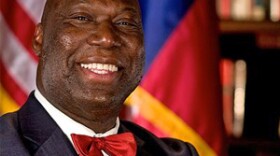

Texas Education Commissioner Michael Williams says he’s heard the complaints and agrees: Schools and student learning need to be evaluated differently.

“My conversations since I’ve been here have gone like this: accountability, accountability, accountability,” he says.

The complex school accountability debate boils down to two key elements: the new STAAR tests students must pass to advance or graduate, and the way those tests are used to grade schools and districts. Bad grades can eventually lead to the commissioner reorganizing or shutting down a school.

Williams ties something else to accountability: the core courses high school students are required to take to graduate. He wants to add options to the course list.

“We ought to be looking at how we can identify math and science courses that have rigor but that fit the fields kids might want to go into,” Williams says. “So everybody still has four years of math and four years of science. But maybe the kid who wants to go into the construction business takes construction geometry. Or a kid that is excited about the possibility of flying people around takes aviation or something like that."

The commissioner says he's asked superintendents to help identify career-focused courses in math and science that he can take to the State Board of Education for approval.

Williams says it’s up to the Legislature to decide one of the most hotly debated accountability questions, whether students are being asked to take too many tests.

But if there are too many tests, he suggests that local districts are complicit.

“There are two different aspects to testing,” he says. “One is the number of end-of-course exams, whether it’s 15 or whatever. The other is the number of tests you take in preparation, the benchmark tests and the worksheet tests.”

He points out that state law limits testing to 18 days, or a maximum of 10 percent of the school year.

“If school districts are testing 40 to 45 days, that’s because they’re doing something quite frankly that is outside of state law,” he says.

But make no mistake: Williams thinks testing is crucial.

“We do measure what we treasure, so it seems to me if we want to make sure youngsters are getting it we must measure.”

The biggest accountability change he’ll pursue may be the way the state rates schools. Superintendents have complained that if just one demographic group of students fails a test -- a specific ethnic group, for example -- then the entire school or district can be labeled unsatisfactory.

Williams says he’s addressing those complaints by expanding the number of ways schools are evaluated to four elements:

- Student achievement on test scores (the current method used).

- Whether schools and districts are closing the racial achievement gap.

- How much scores have improved from year to year.

- How well students are prepared for college or a job.

Williams says the additional measurements will provide more balance to the ratings. He also plans to change the way schools are labeled -- replacing "exemplary/unsatisfactory" with something every student, parent and educator can understand: letter grades of A through F.

“I think they’ll get it,” he said of folks who may find much of the accountability system complex and confusing.