Researchers at the University of Texas at Dallas have built a small, inexpensive sensor they say can tip you off if you're at risk for Type 2 diabetes — the world's leading cause of amputations, blindness and kidney failure.

The wearable device needs only sweat to get readings, even when you're not active. It could be a very big deal for those with Type 2 — that is, if it really works.

No blood or tears, just sweat

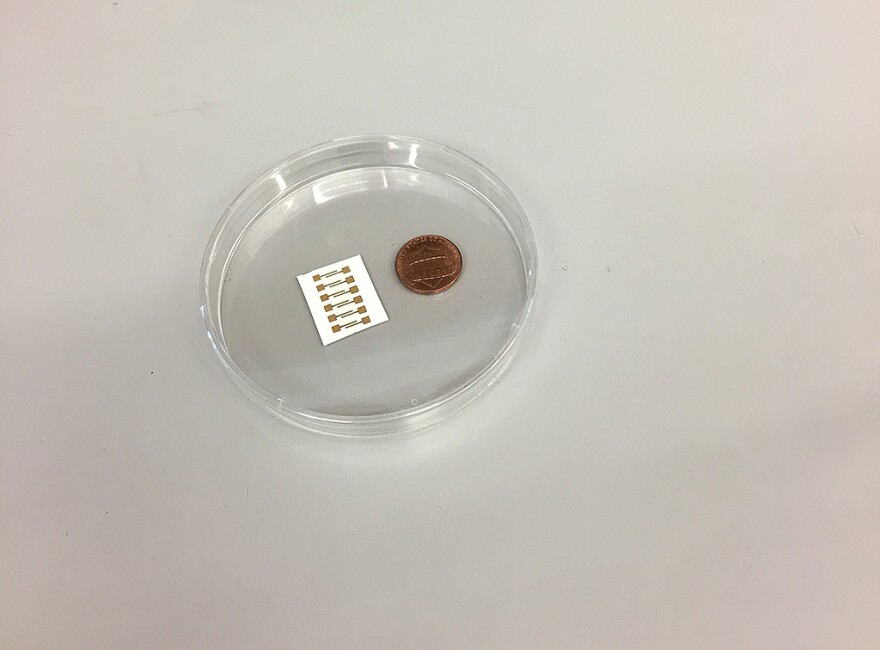

Standing in UTD's bioengineering lab, research assistant Badri Jagannadh is sporting what looks like a pricey digital watch on his left wrist. Instead of telling the time, this device contains a sensor created in this lab that measures cortisol, Interleukin-6 and glucose levels in sweat — numbers you can typically only get with a blood test.

"With sweat, if you can wear it as a watch, it's like, compare it to the conventional glucose meters, where you need to prick," he says. "I don't have to specifically use a finger-pricking device to actually draw and see the measurement."

For years, researchers have failed to come up with a way to read glucose, also known as blood sugar, without puncturing the skin. In the case of sweat, there's usually too much, diluting the result, or too little, and no way to control it.

Shalini Prasad runs this lab and says her team borrowed tricks she learned isolating molecules as an oil and gas engineer to solve this problem.

"If I can modulate that microstructure and then do certain modifications, then it doesn't matter how much sweat my body is going to produce. I can use whatever I produce, take away the excess, or if I have very little, I can spread it better. Most people solve either one or the other; they don't solve for both," she says.

Prasad and her colleagues chose three measurements because she says any change in glucose, cortisol, or Interleukin-6 suggests a person could be at risk for diabetes. She says someone wearing the sensor might see a rise in any of the measurements after eating certain kinds of food and learn to avoid them in the future.

Prasad, who was born in India, would love to take this inexpensive design home, where millions may not even know they have the disease.

"There are 65 million diabetics in India. And India is said to be the diabetes capital of the world," she says. "There is large prevalence but low awareness. How do I increase the reach for essentially just diagnosing people?"

A skeptic's perspective

Diagnosing and treating people with diabetes is Steve Russell's life. The Massachusetts’ General Hospital endocrinologist isn't yet sold on the sensor.

"I think my concern about this whole idea is the relationship between sweat glucose and blood glucose isn't very well established," he says. "I don’t know of a lot of data correlating those two, and it may be true, but that's a hypothesis to be tested."

Russell also questions the choice of measuring levels of cortisol and Interleukin-6, or as he calls it, IL-6.

"To my knowledge, it hasn't been established that changes in the cortisol levels or IL-6 levels for an individual can actually be used to predict whether they will develop Type 2 diabetes," he says.

Granted, Russell wants a reliably accurate diagnostic tool meeting both timely and high medical standards.

Back at UTD, Prasad suggests using this sensor to get accurate averages, say, over a week or more. For example, children could wear the sensor like a Band-Aid.

"And then look at it, even for a month, and say these numbers all are elevated. So then, as a concerned parent, you would go and get your primary care physician to essentially do, then, a detailed battery of tests," she says.

Prasad's convinced she's got something with this wearable sensor. She's still looking for a partner like a pharmaceutical company to pay for more tests, develop a manufacturing plan or even an app for a wearable device.

Doctors like Russell, want a faster, better cheaper way to diagnose or predict Type 2 diabetes. He's not yet convinced that this is it.