On KERA's Think, noted food writer Michael Pollan came to the table to talk about how the things we eat have played a role in the evolution of our societies, economies, and our brains.

All living things are defined by their position in the food chain: What do you eat and what eats you? “Humans are no different,” says Pollan, “except that we get to design our food chain and we operate in more than one. Food imbeds us in the fabric of nature.”

We don’t just exist in nature, though. We shape it just as much as it’s shaped us.

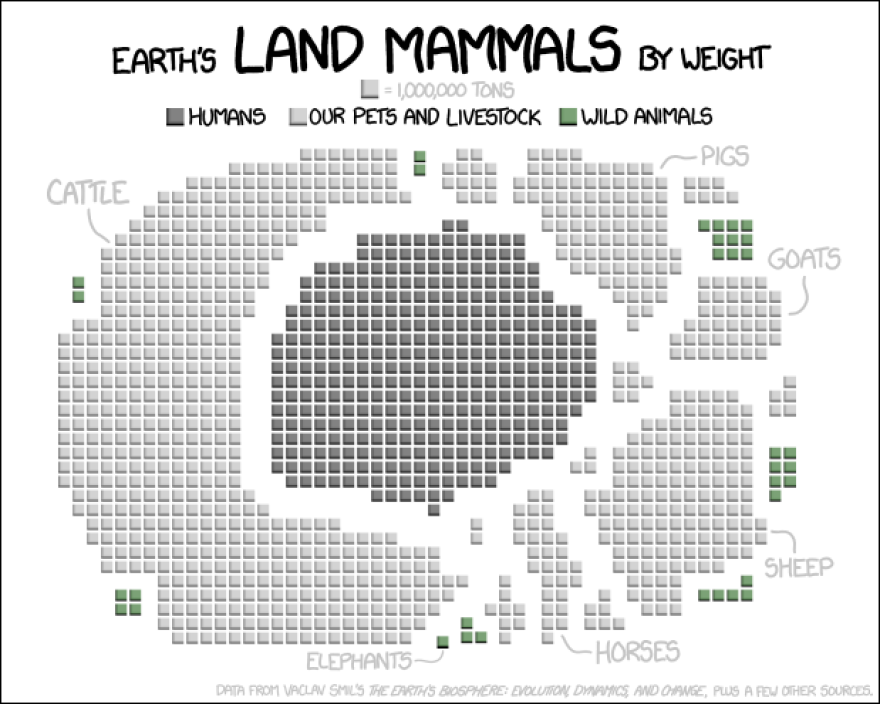

The reason “there are more than 100 million cattle in this country and only 2,500 wolves is because we eat and drink cows and wolves like to do that, too,” Pollan says.

“I couldn’t make a living as a food writer 100 years ago,” Pollan says. “People wouldn’t pay you to tell you where their food came from because they all knew.”

But today, many Americans aren’t aware of their place in this intricate web of who-eats-who.

It helps us to be more conscious of what’s at stake when we eat. There’s been a boom in home gardening in general, thanks in part to Michelle Obama and her White House garden. There’s a website that maps fruit trees in the public domain:

The Falling Fruit Map is a guide to the "urban harvest" of edible plants in the public domain. Zoom out to see map plots around the world.

Our understanding of food continues to evolve. We really don’t know much, Pollan says. Today, nutritional wisdom upholds the value of minimally processed, “whole” foods. “Food is greater than the sum of its parts,” Pollan says. “Reducing food or drug plants to a single magic ingredient is to miss something.” In other words, structure matters, too.

Vegetables are beneficial primarily because of the fiber in their cell walls, not only for their nutrients. Fiber, though chemically simple, is vital to maintaining our microbiomes. “We can’t just focus on feeding ourselves, but the whole collective that is ourselves: us plus 10 trillion bacteria,” he says.

Diet fad as distraction

“There has always been an evil nutrient,” Pollan says, “and right now, it’s gluten.” The incidence of celiac disease and other gluten intolerances does not match the size of the market for gluten free foods. Pollan says this is nothing new. But these mass misconceptions can affect major health trends down the line.

In the ‘80s and ‘90s, nutritionists advocated reduced fat intake. Ironically, during this low-fat campaign, we got fat. “People binged on anything that wasn’t fat,” Pollan says, “and that tended to be refined sugar and white flours.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LGJNtgpvcM4

A 1993 Nabisco ad for Snackwell, a line of popular fat free cookies and origin of the “Snackwell Effect"

But all this constantly evolving advice has become a way to avoid the conversation Americans notoriously ignore: quantity. When we add something to our diets, it should replace something else. “You can get fat on very healthy food if you eat enough of it,” Pollan says.

The urge to gorge ourselves has deep evolutionary roots: Humans evolved in an environment with fluctuating periods of famine. Our ancestors survived by storing energy in the form of fat. For many of us today, however, the famine never comes.

The cost of efficiency (and budget cuts)

It’s not only nutritional wisdom that changes. Since the post-war period, Pollan says, the food chain has been lengthened and industrialized. We’ve become more efficient at producing food, but not without costs. Factory farming has left an indelible mark on our foodways — especially in rural communities.

Trump’s budget included big cuts to programs that farmers and rural communities depend on, like crop insurance and food stamps. “We know that in the absence of food stamps people are much less healthy, and therefore much more expensive to take care of,” Pollan says.

Last week, the president proposed food stamps be partially replaced with prepared food boxes, which would not include fresh food. Pollan has concerns over the idea. Similar programs in the past have had many logistical challenges, and moreover, take away people’s ability to choose what they eat.

Legislation on food stamps doesn’t just affect the people who depend on them to eat. Pollan says that Walmart depends so much on food stamps, sales fluctuate closely with the program’s disbursement dates.

Pollan’s forthcoming book is How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence. You can follow him on Twitter here.

More on Think with Krys Boyd

- Listen to Krys Boyd's Feb. 19, 2018, interview with Pollan

- Listen to episodes about food

- Listen to episodes about health

- Subscribe to the Think podcast

Megan Zerez is an intern at KERA.